Passion Week: Palm Sunday

Walking with Jesus through Passion Week

March 24, 2024 — Samuel Hood

After Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, the religious leaders became exceedingly nervous about Jesus’ influence on the crowds. If they were ready to make Jesus king after he multiplied the loaves and fish and fed five thousand people (John 6), how much more would they proclaim him to be the Messiah after he raised a person from the dead (John 11)?

The religious leaders are all the more terrified, because the time of the Passover is at hand and thousands of Jews are flowing into the city of Jerusalem to celebrate God’s deliverance of Israel from slavery (John 11:55). They have reasons to be concerned. What will happen when these people begin to hear that there is a man who not only teaches the law with great insight and authority, but also works miracles and has power over sickness, infirmity, demonic powers, and even death? These circumstances have the ability to incite messianic fervor, something that will surely disrupt the political and religious powers that be.

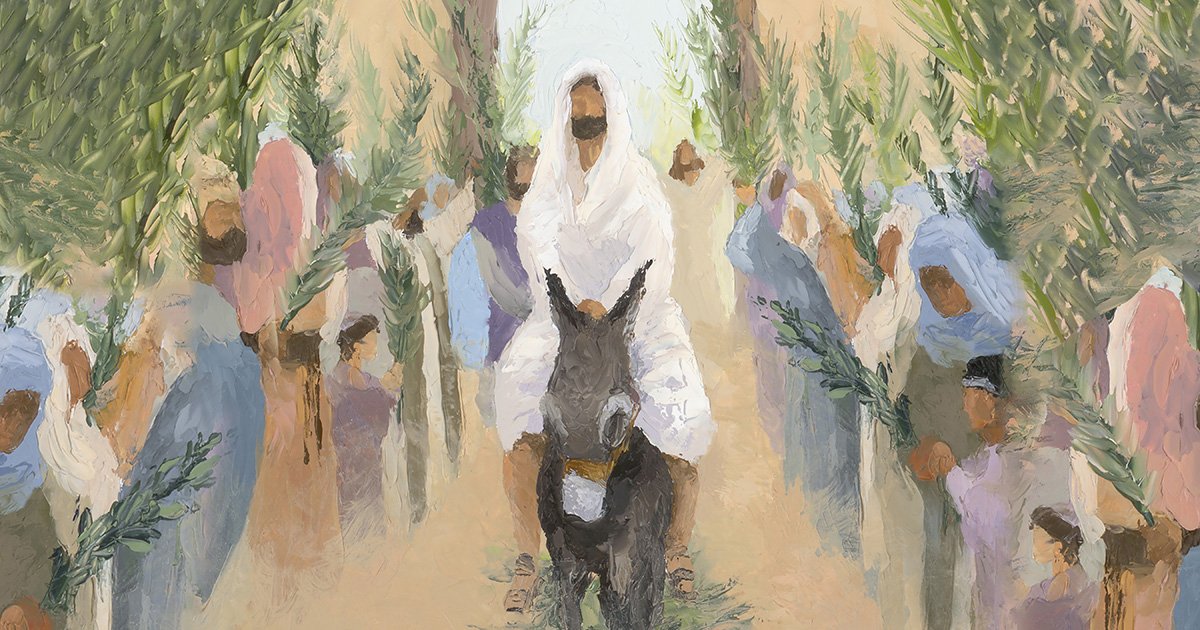

Thus, as Jesus rides into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, there is an intentional contrast in the text. Many of the people want to make Jesus king, but the religious leaders want to make him a dead man.

The deeper reality of the story is that Jesus knows that He is going to die as he rides into Jerusalem. This is not simply because he can read the political weather, but because this is his very mission. He has come to Jerusalem, in God’s sovereign plan, to die.

As the people wave palm branches and shout “Hosanna” (John 12:12-13), they are communicating that they believe Jesus is king. Palm branches, in the ancient world, signified a military triumph or royal acclamation. This is exactly what the Jewish people did when the Jewish messianic figure, Judas Maccabeus, drove out the pagans from the temple in 164 B.C.E. and restored Israel for a short time. They waved palm branches. They declared that Judas was their Messiah.

As you read the story in the Gospel of John, there are many differences between Jesus of Nazareth and traditional messianic figures like Judas Maccabeus or traditional Roman emperors like Augustus Caesar.

When Jesus rides into Jerusalem as king, he does not ride into the city on a horse. He rides in on a lowly donkey’s colt (John 12:15). In other words, he does not come into the royal city with the imagery of a military leader or conqueror. He comes in lowliness, humility, and peace.

And as the story unfolds, Jesus does not wear a crown of gold that a king would wear. He wears a crown of thorns (John 19:2). His crown symbolizes solidarity with human pain and suffering.

When Jesus is empowered as king, he does not sit upon a royal throne. Rather, he is enthroned upon a Roman cross — an instrument of torture and shame. Jesus’ kingdom is defined by radical sacrifice and self-giving love.

Jesus is not like any other king, whether Jewish or Roman. He is humble, meek, peaceful, loving, self-sacrificial, full of compassion and mercy, and willing to suffer and be in solidarity with all the marginalized and hurting in the world. There has never been a king like this in the history of the world. There has never been a king like this that is also God in the flesh (John 1:14).

Later in the Gospel narrative, Pilate looks at the people in Jerusalem and says, “Behold, your king,” (John 19:14). Within the story, this statement echoes with both irony and tragedy. But within the pages of Scripture, it resounds with confidence and theological clarity. When Jesus hangs upon the cross, the lowest low of human weakness and shame, this is a vision of the highest heights of divine strength and glory.

It is the mystery of the ages containing a hidden wisdom and beauty beyond human philosophy and creative imagination. This Jesus of Nazareth rides into the royal city of Jerusalem on a donkey, bears a crown of thorns, marches up the stairs of Golgotha, and sits upon a cross-shaped throne. He is the Lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world (John 1:29). He is our king.